Douglas McGrath's play at the Vineyard tracks Richard Nixon's tragically crooked career

I always associate Richard Milhous Nixon with Halloween: He was a haunted man. A memorable cartoon by the Washington Post's

"Herblock," during Nixon's 1972 presidential campaign, showed him as a

harried householder, fending off the trick-or-treating of five

persistent little ghosts, their mud-smeared sheets labeled "Nixon 1948,"

"Nixon 1952," and so on. The image raises tears as well as laughter:

Nixon's political life was a tragedy for him as much as for the nation.

Though a repellent personality, and probably the most dishonest president we've ever had (with the arguable exception of George W. Bush),

Nixon deeply longed to achieve both greatness for the U.S. and a high

place in history for himself. Instead, he nearly wrecked our country and

did a more thorough job of destroying himself than his worst political

enemies had been able to accomplish in three decades of trying. (When

the Watergate tapes were revealed, the New York Post's full-page headline rang true psychologically as well as factually: NIXON BUGGED HIMSELF.)

Douglas McGrath's Checkers (Vineyard Theatre) starts and ends with Nixon (Anthony LaPaglia)

being prodded to make that 1972 electoral bid, as a framework for the

1952 story that particularly haunted Nixon: his first brush with

nationwide campaigning, as running mate to Dwight David Eisenhower,

the World War II military hero who, after years of strategic

vacillation while both parties wooed him, had finally consented to a run

for the White House as a Republican.

Ike, who had little appetite for political infighting, and Nixon, who

had clawed his way into the Senate through a variety of below-the-belt

tactics, made a decidedly odd political couple. Eisenhower campaigned on

his military glory, while Nixon, sniping at the fiscal scandals and

alleged Communist sympathies of the Truman administration, functioned as

his attack dog. As Eisenhower insider Herbert Brownell (a wonderfully crisp, oily performance by Robert Stanton)

tells Nixon in McGrath's script, "Generals stand in the sunlight on the

hilltop. You're the soldier. You sling the mud and the shit."

The difficulty lay in the shit potentially sticking to Nixon himself:

a comfy personal-expense campaign fund, put up by his wealthy

right-wing supporters. Though not strictly illegal, this also wasn't

strictly an ethical practice. With reporters asking increasingly nasty

questions, Eisenhower's handlers, in confab with Nixon's adviser, Murray Chotiner (juicily played by Lewis J. Stadlen), decided that Nixon should go on national television to clarify the matter.

The result, commonly known as "the Checkers speech," was both a

pivotal moment in television history and a consummate piece of

tricky-Dickery, combining hollow protestations of innocence and subtle

slurs on his accusers' motives with an awesome battery of tear-jerking

gimmicks, climaxing in his confession that he had improperly accepted a

gift, from a donor, which he vowed he wouldn't return—Checkers, a cocker

spaniel pup adored by Nixon's little daughters. The gimmick triumphed:

Sixty million viewers wept over the kids having to lose their dog.

Eisenhower, who had contemplated kicking Nixon off the ticket, was stuck

with his tarnished running mate.

McGrath strives, often successfully, to show the elements in Nixon's

tangled psyche that led him to the groundbreaking speech and on into the

rest of his mucky career: his sincere desire for what he perceived as

the country's good; his warped willingness to get power by any means

necessary; the poor-kid resentment that simultaneously viewed the

nation's elite as an exclusive club forever snubbing him, and its masses

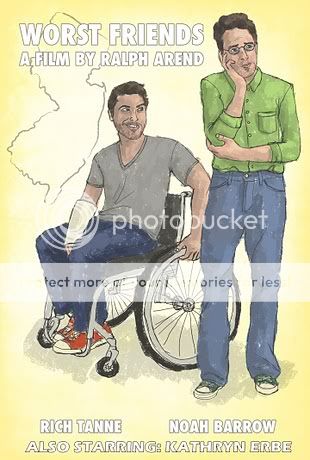

as ethnic scum to whom he was superior. McGrath sees Nixon's wife, Pat (Kathryn Erbe),

as essentially virtuous in her loathing of her husband's dirty

politics, a Jiminy Cricket-like conscience who sticks by him despite his

constantly broken promises.

Uncertain in its dramatic structure—a string of short scenes with little overall shape—as well as its focus, Checkers nonetheless gives a fascinating view of its screwed-up central figure. Terry Kinney's direction, handling the intimate scenes sensitively, keeps its pace up between scenes thanks to Darrel Maloney's

vibrant animated projections. Erbe is consistently touching, but it's

LaPaglia's riveting impersonation, capturing Nixon's slouch, jumpy body

language, and slightly thick speech to perfection, that makes Checkers an event rather than a mere commentary on the Republican party's poisoned past.

No comments:

Post a Comment